The aim of this article is to promote a new approach to playing tennis: the levels approach.

It will shortly be defined. The motivation for learning this approach is that it offers the following:

- Offers a new insight into watching and playing tennis further than the layman approach of just watching the game and seeing it how it is.

- Allows you to make predictions on player’s (and your own) performances and see how player’s react to pressure in matches.

- Takes the frustration out of playing tennis: this approach explains how to deal with unforced errors, double faults, and further negative

- features and how to understand them in the greater perspective.

This approach came to mind after a discussion with a coach during the 2012 Wimbledon match, Lukáš Rosol versus Rafael Nadal. To recall how well Rosol played, the highlights of some his best rallies are linked below.

Towards the end of the first set, as we discussed the momentum swing going from Rosol to Nadal and as a result, Nadal taking the first set, the coach says “if Rosol loses this set, he will win the match”.

This seemed bizarre. Surely Rosol should win the set to win the match? In his eyes it was different, when asked to explain his comment he offered the following explanations:

- Nadal gave his maximum effort to take the first set and in doing so, took a physical toll on him and his ability to play later on in the match. Rosol was playing well but as he said himself , he was in a trance and had no problem about worrying what would happen later on if he immediately exerted maximum effort: his big serves would give him free points which would allow him to recoup the mental energy required to win rallies against Nadal, which is difficult to do so, as explained by the article here.

- When Nadal loses sets his effort increases as the match develops, to not allow the opponent any rhythm and to make winning against him much harder. But after a hard fought set in which he was out hit yet still captured it, it is expected for Nadal to think slightly differently (even if just about every commentator says that Nadal plays one point at a time) as to how he would had he lost the first set. As Rosol was in a trance, this made no real difference and his motivation stayed.

- Rosol “handled” Nadal’s all by losing a close set. He understood what was successful and what could be improved. On the other hand, Nadal won the set despite being out hit and at times, out played. Nadal was not getting completely schooled, therefore it is expected for him to have not been so worried about his approach as he took the set.

As the match developed, Rosol kept hitting big and overcame Nadal’s efforts. This can be seen as some sort of a level (a position on some quantity). Rosol’s level withstood Nadal’s level. Nadal’s level could not stand Rosol’s level and when he tried to do so, the match was still out of his hands.

This example gives a good guide to what the levels approach is. Formally, a player’s performance in a match is based on many factors – footwork, movement, groundstrokes, serving, physical condition, mental ability. These factors combined into a performance give a player a level: an explanation on how the player performs.

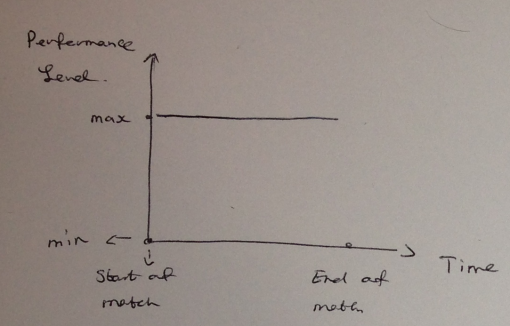

We can show this graphically by considering two axes: the time of a match and the performance level of a player. We will look at some examples and analyse.

Example 1: Constant Level

The “min” refers to a players lowest possible performance level and “max” refers to their best. Clearly if they can play at their best throughout a duration of a match – they should produce their best possible performance. Note that as time increases, which means factors such as the crowd, opponent’s strategy, tiredness, weather and so on all change, the level of performance stays the same hence the name “constant”. This is what tennis players dream of – to not be reactive to any situation.

For all practical purposes this is unrealistic, rarely do we (or professional tennis players) perform our best for a whole period of time at our job or any activity. We make mistakes, perform tasks with some worries or trouble and so on. Does this mean perfection does not exist? This question is hard to answer. But we understand that the image above is realistic. The best we can hope is to keep playing a good level through out a match. This is done best by preparation (which will itself be a future article).

Specific player:

Lleyton Hewitt is a player who maintained his level through out matches. His levels approach (to stay consistent, recall that other players of Hewitt’s height have been far more aggressive) brought him two majors and the world number one rankings as a teenager. This has several implications.

- Clearly his levels approach is successful and aiming your level to not go up and down too much is a strategy worth pursuing. When Larry Stefanski coached Andy Roddick, many fans complained that Roddick had become a pusher – that his big forehand had gone and he was playing far too tactical. These opinions can be explained by Stefanski making Roddick’s level far more consistent. In his approach, he had less up – less big shots, but he also had less down and for Roddick there were many more downs: his awful slice approach shots, weak “puffer” backhand shots, bad court positioning and so on. His level became more consistent and with an increased physical fitness, he enjoyed a brief spell of extreme success in 2009 before players adjusted to his tacics.

- Hewitt achieved so much at a young age – his approach is beneficial to young players as they do not have to figure out how to manage their big aggressive games. Roger Federer gives a great explanation to the difference between him and Hewitt in this video, in 2002

This level approach also has shortcomings. In fact any level approach has shortcomings (just like how it has benefits), it is how the levels approach matches up against another player’s level approach. This determines success.

Does my levels approach, say Hewitt like, being consistent, beat an approach of someone like Alexandr Dolgopolov, which is up and down to the maximum?

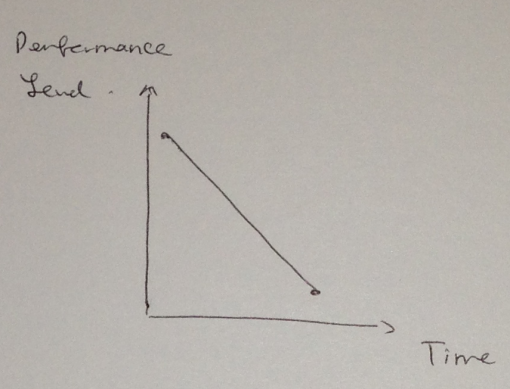

Example 2: Up -> Down Level

This approach seems obvious. A player starts out well and his level is good: he has cut out the negatives in his game. As time proceeds he cannot keep this level up or the opponent starts to play well and he begins to decline – his level drops. Then the opponent is in a better position and surely wins the match?

That type of thinking is certainly possible – a five set match in which one player is up two sets to love and loses three sets to two can be a good example of this level, but it is not the only explanation. This is a subtly with a player’s level: perceiving is half of the analysis.

What if the player is facing an opponent like Hewitt, who keeps his level constant? Then it is not immediately obvious why the level drops. Even more absurd: it is possible for a player to win a match even as his level drops incredibly. A good example is the following match between Roger Federer and Robin Soderling at the 2009 US Open. Federer’s form in the first set is incredible but it begins to drop. He closes out the match in the fourth set, despite Soderling playing very well in the fourth set and Federer not capturing the form in the first set.

This happens as the position the player with the high level has put himself is in dominance: the opponent must raise his level (to some extent) to come back where as the player is allowed to drop his level as long he wins the match and wins the important points.

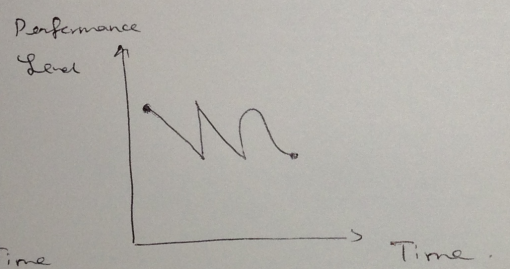

Example 3: Crazy

The levels here may seem crazy – you have somebody playing well, then going downhill, suddenly they are hit by lightning and improve, then fade away again before a smoother final change. It seems a bit crazy.

The reality is that we really play like this – no one (unless you’re a young Ernests Gulbis or Marat Safin) wants to lose a match. We try our best. Our levels dip in response to the other person. This examples shows what a normal match looks like – it can be a hard fought 7-6 7-6 win or a crazy 6-0 0-6 6-0 thriller.

We conclude with how you can use the levels approach to understand tennis further and how it can be used for your own game.

When watching matches look at the player’s game styles and what they have to offer – look at how they are handling their level (observe how Andy Murray swearing drags his level down). Then if a player can handle his level whilst the other is playing better, they can win a match without being the best. Nadal is a great example – he can take the best a player gives to him, give them a few points where they play their best but soak up all the other points. He accepts an opponent playing some unbelievable points and allows his level to dip at these moments. Then his level raises again and he keeps asking for his opponent to remain at their higher level.

Understanding that your double faults and unforced errors and other frustrations bring your level down and make your opponent’s life easier makes you appreciate to keep your emotions in check. Further, there can only be an improvement in your level after you start cutting out the frustrations. Your game is vastly improved as you begin to consistently increase your level. If an opponent is playing well at some point and all appears to be hopeless – remember the levels approach. He may win that set 6-0 and completely dominate you, but you may scrape the next set 7-6. Absolute opposites can become near similarities by understanding how to shift your level.

This means you take what you are good at, make it so that as your level drops, that it remains good. New tactics become ingrained, new shots become regular and new found confidence becomes the norm.

P.S. I would like to say thank you to all the people who have read my blog, all views and comments are appreciated, I read them all. If you would like me to do a post on a specific topic – just mention it by leaving a comment.